I was born three years after my parents gave my foster sister back. As far as my mother was concerned, I replaced her. My father, I’m not so sure. Josie would have been about six by then. My brother, Marc, was seven. I grew up without knowing the first thing about Josie’s existence.

Only as an adult did I trip across the one photograph that my parents seemed to possess of her. There, tucked into some ancient album, appeared a small blond stranger stepping down Fifth Avenue between my equally small older brother and our fashionable mother. Easter, 1949, the caption read. My mother wore a black veil, white gloves, and a fox stole with its jaws biting its tail to secure it around her shoulders. I recognized the fox, which still hung in the coat closet. I recognized my brother and mother, though I’d never known them so young. But who was that other toddler?

“That’s Josie,” my mother informed me. “She was our foster child.”

Josie with my mother and brother, NYC, 1949. Image: author.

“We had a foster child?” Every word of that sentence sounded improbable. I’d always thought of foster parents as souls of generosity, caring people who volunteered at school events, played ball with their kids, and turned up with casseroles at community potlucks. However off base that stereotype might be, it in no way described the parents I knew, who much preferred gala events and cocktail receptions at the United Nations, where my father worked, to anything directly involved with children. I can’t even recall my mother ever reading to me as a kid. And my father’s commute — over an hour each way from our home in suburban Connecticut — removed him from my foster parent projection almost entirely. But then again, the photo was taken when my parents still lived in Manhattan.

“How long?” I pressed my mother, who was gazing at the photograph with an expression I couldn’t fathom. A certain strain around the eyes, tenderness around the mouth.

She inhaled deeply, suppressing whatever thoughts had formed. “I think it was about two years.”

“Two years?” I bit back the obvious question. My mother could take offense at the subtlest shift in voice, and her blowback would send me reeling. So instead of asking how she could have simply erased this child of two years, I invited her to tell me the story.

Her version went something like this: Josephine Wing was half-Chinese and half-Swedish. In 1948, her alcoholic mother, the Swede, and her ineffectual Chinese father surrendered Josie and her older brother to Sheltering Arms Family Services. My brother’s pediatrician, Dr. Hedwig Koernich (who also took care of the Kennedy children, my mother made sure to add), was on the board of Sheltering Arms. When the Wing siblings arrived, Dr. Koernich immediately thought of my Shanghai-born Chinese father and my Wisconsin white mother, mostly because of their races but also because they had a little boy about the same age as Josie.

“But you didn’t take Josie’s brother?”

My mother dismissed the thought with a roll of her hand. “Josie hated him.”

Josie wasn’t even two years old. I hardly think she had any say in the matter, but my mother’s deflection didn’t surprise me. She’d never take on more than she could handle — or control.

“Two years is a long time,” I said. “What happened? Why didn’t you keep her?”

“Oh, we wanted to.” My mother’s eyes welled up. “I had miscarriage after miscarriage, and I desperately wanted to adopt Josie. Her creep of a mother refused.”

“You know what happened to her?”

“No.”

“Did you ever try to find out?”

“What would have been the point?”

When I asked my father what he remembered about Josie, he just shook his head.

* * *

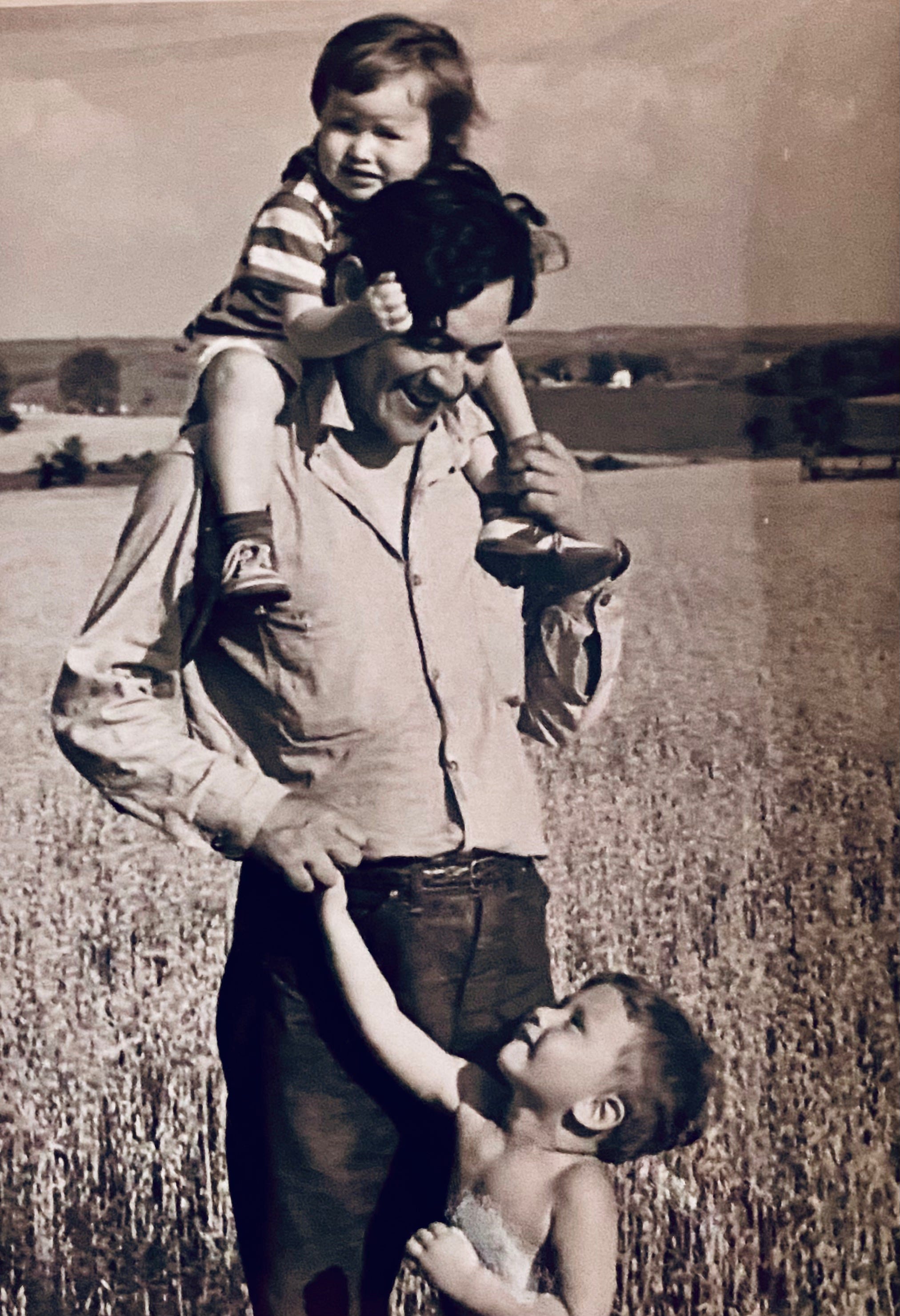

In the absence of any pictures of my father with Josie, I imagine them in their apartment on 92nd Street, meeting over what passed for breakfast, the same way he and I used to meet.

1948. My dad 36 years old. Early morning, before he goes to work, dressed in suit and tie, polished black Oxfords tightly laced. He’s lived in America since he came to California for college, but his first 19 years were spent pivoting between his Chinese father’s expectations and his American mother’s demands. His father was a government official, a Chinese scholar and classical poet. His mother was an American wife who lived in China for two decades and never learned the language. Dad split the difference by following the lead of the British who ruled his school and pretty much everything else in Shanghai. That included acquiring a taste for English muffins like the one he’s now toasting and layering with butter and marmalade. Josie hugs the doorway, watching, silent and alert.

My mother, never an early riser, would be sleeping. My brother? Playing with toy cars, no doubt. Models would become his hobby, then rebuilding engines, then buying and selling rehabilitated getaways. So it’s only Josie in the kitchen with Dad this morning as the sun slides in, painting the linoleum orange.

He gives her a piece of his muffin, and she stuffs it into her mouth but chews it very slowly, never taking her eyes off him. Sticky hands now. Bare feet and smocked pink flannel nightgown. Such a funny little thing, Dad thinks. Those blue-black eyes and Dutch boy hair, yet strangers never doubt you’re mine.

* * *

Over the years, my mother will say that Josie worshiped Marc. My brother says he doesn’t have any memories of her, but the resurfaced story got to him, and he named his third daughter after her.

That naming spurred a richer, darker account of Josie’s delivery to Sheltering Arms. The Wings had evidently planned to move from New York to Florida, transporting their children and all their worldly goods in a beat-up station wagon. Neighbors called the cops when they spotted the parents loading Josie and her brother into a pasteboard box tied with twine to the top of the car.

Was the mother on a bender? Was her coward of a husband just following orders? Or was this his idea of saving space and avoiding the headache of his wife’s complaints about the kids on their long drive south? Maybe the whole thing was one sudden impulse. Maybe the brother made a fuss as they struggled to load him in. Maybe he sat up and cried, or just waved his arms to attract attention. At two or three, he might have realized what Josie couldn’t, that something about this container didn’t feel right. Maybe he saved both their lives. Or maybe it was just blind luck that prompted a good Samaritan to alert the cops. Nobody got out of town that day, but the kids got out of that box. The police took them to Sheltering Arms.

“Can you imagine anything so ghastly?” my mother demanded when she revealed these details.

I couldn’t at the time, though they bore an unsettling similarity to the later media reports of presidential candidate Mitt Romney driving for 12 hours with his Irish setter Seamus in a pet carrier strapped to the roof of the Romneys’ Chevrolet Caprice wagon. And all hell broke loose over that.

My uncle, who’d visited my parents in those early days, remembered something even more sinister about Josie. “That poor little thing,” he told me. “Her skull was all flat from lying on her back before they got her, and her toes curled inward.” For more than a year, it seemed, Josie’s parents had kept her swaddled tightly in a drawer and rarely took her out of it. Her feet pointed like a ballerina’s. When my parents received her, she must have been about fifteen months old, but she couldn’t even crawl and barely made a sound.

“Oh, she was tearing around in no time,” my mother assured me. “She would do anything to keep up with Marc.”

But my brother, like me, is a quarter Chinese. Dad, like Josie, was half. And it’s him I keep seeing with her. Two of a kind, the two of them. Both half and half. Dad must have marveled. Despite her fair hair cut like a little Dutch boy’s, despite neglect far greater than he’d ever known, Josie still had more innately in common with him than his wife or son or future me. Worlds apart from the world around them and yet also boxed in.

* * *

After Josie had been with them a year, it was time to start thinking about school. According to my mother, everyone said that city schools were dreadful.

I doubt that Dad knew who “everyone” was, but he knew better than to contradict his wife when it came to the children. “Everyone” also said the schools were reliable in Connecticut, and in towns like Cos Cob, just outside Greenwich, houses were cheap and taxes low. So they drove out to take a look.

My mother has described this life-changing day to me so often, I can easily follow it through her eyes. Only recently, though, did it occur to me to imagine how the post-war suburbs must have struck my Chinese father, who’d grown up in a city where parks bore signs reading “No dogs or Chinese.”

As they passed through Greenwich, Dad surely would have noticed the rolling green lawns, towering oaks, and ubiquitous steeples, pale young housewives pushing post-war buggies and trailing distracted towheads. This was the era of Madison Avenue, the man in the gray flannel suit. On weekdays, these scions of the suburbs would migrate on schedule into Manhattan, but how could my father have envisioned his face among theirs? The crowded trains of the New Haven line may as well have been marked White Men Only.

I picture my father driving with the top down. By all accounts, he was besotted with his dark green ’37 Buick. He’d bought it during the war, driven it up to New York from DC. Turn on the radio, roll down the top, press on the gas until everything past and present faded into the future.

That was a lie, of course. The past always catches up.

And the car was different with passengers. His wife riding shotgun, two kids in back — Marc kicking and squirming, and Josie coughing in her sleep.

The leaves were turning bright, though it was warm for fall. The Mianus river sparkled to the right.

“Bet that freezes in winter,” my mother said. “Wouldn’t it be fun to skate on? We used to skate outside Milwaukee. You can go for miles, and people build little fires along the shore and have hot chocolate. Ever skate like that in China, Moe?”

He searched for the drive, the steep hill to the left that the realtor had described.

“Maybe it never got cold enough there.” She tried again.

“It gets cold enough.”

Skate on rivers through the Warlord Era, between famines, floods, and beheadings. My mother’s passion for romance and ignorance of history might have charmed Dad in the beginning. Now, what could he say?

A rusted nameplate jutted from a massive rock outcropping: Lia Fail.

And she was off again. “The real estate lady said it means Stone of Destiny. Like the Blarney Stone. Some kind of Irish or Celt. I love that, don’t you? To get to our place, turn left at the Stone of Destiny!”

She laughed, and they turned up a steep and narrow lane into the wooded estate where my parents were indeed destined to buy two acres of land and build the house where they would live for the rest of their long lives.

The house in Lia Fail. Photo by author.

* * *

Fifty-seven years later, as my father lay dying in the house that they built, he asked me to bring him a cash box that he claimed contained $2 million. He was not in his right mind. My mother dismissed the claim of fortune out of hand. I agreed it was most likely a delusional request, but I nevertheless kept searching.

That oversimplifies the process. My father had turned into a hoarder over the years. His office was packed solid with plumbing supplies, Chinese mementos, ancient bills, tattered clothes, unused Christmas gifts, appliance manuals dating back to the 1960s. Over the last two weeks of his life I peeled, poked, dove, and sifted through countless cartons, crates, suitcases, paper bags, and leather trunks. I found treasures in the form of old letters, scrapbooks, pictures from China, but not the box Dad wanted.

He’d been dead for ten days when I found it. Squeezed into the rear corner of a six-foot-deep boot closet, a black metal box sat as if it had just been waiting for me to turn up. It looked like a cash box but the surface was pebbled. Fireproof, it was meant not for cash but for film.

“Got it!” I yelled, backing out of the waist-high closet.

My 87-year-old mother appeared at the top of the living room steps, one hand covering her mouth. She used the rail to support herself as she descended.

It was a sweltering August morning, but the box was cool to the touch — and unlocked. I placed it on the entryway table and lifted the lid.

Inside we found hundreds of photographs of a little girl, aging from two to four years old, with straight blond hair and almond eyes.

“Josie,” my mother breathed.

Photos of Josie. Image by author.

The foster child. The one I replaced. The one who might have replaced me, if my parents hadn’t given her back. But that came later. Now, here’s Josie with my brother and mother sledding in Central Park, sitting on Dad’s youthful shoulders as both of them beam, marching through the Connecticut woods where my parents would build their family home, riding a tractor on my mother’s parents’ Wisconsin sheep farm. Here’s Josie with blond hair cut like the little Dutch boy and eyes that match my father’s.

My mother is mystified by the cache. “After we lost her,” she says, “I never heard him utter her name. Even when she lived with us, he hardly seemed to notice. I mean, he was nice to her…”

As my mother now tells the story, “We did everything in our power to keep her.” But the laws of New York did not allow them to take her out of the state. They hadn’t realized that when they took her to visit my mother’s parents in Wisconsin. They didn’t know they were breaking the law on the fateful day when they drove out to Connecticut to discover the Stone of Destiny. There were no consequences or even warnings until they informed the social worker they were moving.

“We tried to adopt her,” my mother repeats. But Josie’s mother refused.

“We’d already started building the house,” my mother says, fingering the photographs of Josie and Marc playing on the slope of rock that now frames the hearth beside us.

The house, or the child? Images: author.

They had to choose between the house and the child. They chose the house. My mother’s house. Which, at the time of my father’s death, was valued between one and two million dollars.

Mom’s never denied that the move to Connecticut was her call. My father would have stayed in Manhattan forever. They never would have lost Josie, if it were up to him.

“Losing that child broke my heart,” my mother insists. But after the move, she still had my brother, and soon she became pregnant with me. Life rolled forward, and she never thought to ask what my father so clearly had.

My father with Marc and Josie, 1948. My grandfather in wartime China, 1942. Images: author.

Because Josie wasn’t the only one. When he left China for the last time in 1942, Dad also left his father, never to see him again. When the Communists seized China in 1949 and the borders closed, my grandfather disappeared. Dad never learned what had happened to him, when or how he died.

How do you live without those you leave behind? How do you live with yourself for leaving them?

You keep them, I hear my father crying. You keep them all.

Aimee Liu is the bestselling author of the novel Glorious Boy, as well as Flash House; Cloud Mountain; and Face. Her nonfiction includes Gaining: The Truth About Life After Eating Disorders and Solitaire. Aimee's books have been translated into more than a dozen languages. Her short fiction has been nominated for and received special mention in the Pushcart Prize competition. Her essays have appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, The Los Angeles Times, Poets & Writers, and many other periodicals and anthologies. Subscribe to her substack here for more updates.

This essay was nominated by a Pushcart Prize by Flat Ink.

Editorial Art by Dilara Sümbül